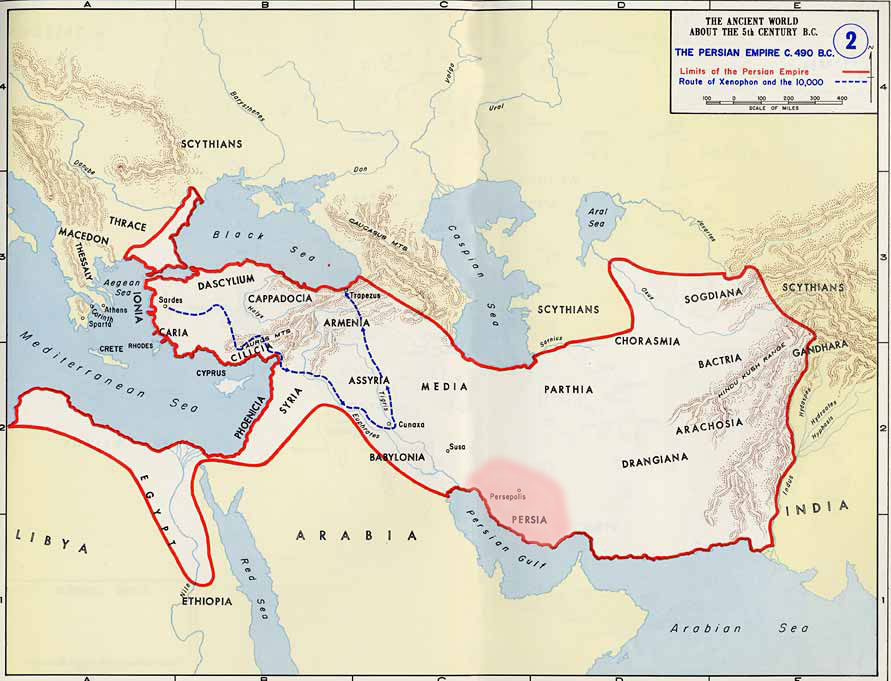

The growth of Persian power had begun when Cyrus (ruler between 560-530 B.C.) established himself as the first Persian king. Previously, the Persians had been ruled by the Medes, a related people whose original territory occupied what is now northern Iran. The Greeks indeed often used the term "Mede" to refer to Persians. The ancestral homeland of the Persians themselves was found to the south of what is now the country of Iran. The Iranian language of today remains a descendant of ancient Persian, in contrast to the Arabic now spoken in neighboring Iraq and other countries of the Near East.By the reign of Darius I from 522 to 486, the Persian Kingdom had expanded to encompass a vast territory of heterogeneous populations stretching east-west from what is now Afghanistan to Turkey, and north-south from the southern territory of the former U.S.S.R. to Egypt and the Indian Ocean. The Persian king governed this immense area through a system of provincial organization, whose chief administrators were governors, called satraps, like the one whom the Athenian ambassadors met in Sardis. A satrap was a powerful figure in his own right, ruling over his province like a monarch.

By 500 B.C the Persian Kingdom had millions of subjects. The Persian kings exacted taxes from their many subject peoples in different ways in different regions. Tax revenues could be levied in the form of food stuffs, precious metals as bullion or coinage, and other valuable commodities. The various provinces were also responsible for supplying soldiers to staff the royal army. The material and human revenues of the immense kingdom made the Persian kings wealthy beyond the Greek imagination. Although the Persians did not regard their king as a god, everything about him was meant to emphasize his grandeur and superiority to ordinary mortals. His purple robes were of the most splendid fabric; red carpets were spread for him alone to walk upon; his servants held their hands before their mouths in his presence to muffle their breath so that he would not have to breathe the same air; he was depicted as larger than any other human being in the sculpture adorning his palace. To display his concern for his loyal subjects, as well as the gargantuan scale of his resources, the king provided meals for some 15,000 nobles, courtiers, and other followers every day, although he himself ate hidden from the view of his guests. The Greeks, in awe of the Persian monarch's power and lavishness, referred to him simply as "The Great King." (From Thomas R. Martin, An Overview of Classical Greek History from Mycenae to Alexander)