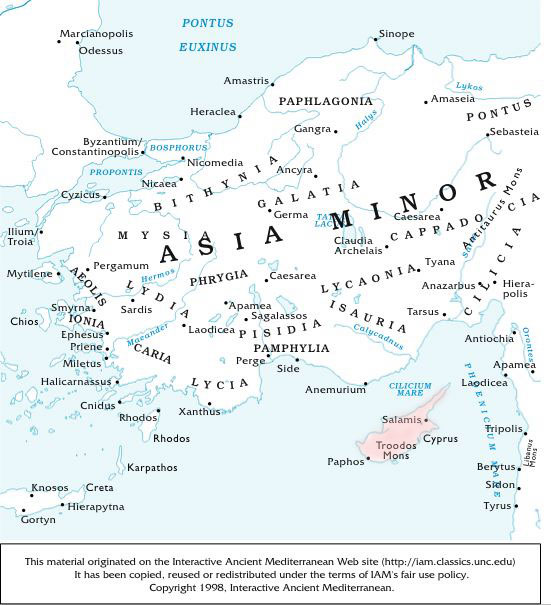

A large island of the Mediterranean, south of Cilicia and west of Syria, identical, at least in part, with the Hebrew Kittim, which seems to be its oldest known name; but it appears to be sometimes included in the name Caphtor, a title that properly belongs to Crete with other islands and coast lands settled by the Caphtorim. Other ancient names of Cyprus, most of them poetical, are Aeria, Aerosa, Acamantis, Amathusia, Aphrodisia, Aphelia, Collinia, Cerastis, Cryptos, Meïnis, Ophiusa, Macaria, Paphos, Sphekeia. The derivation of the name is uncertain, but the principal authorities, ancient and modern, refer it to the Hebrew kopher or gopher, the name of a tree; sometimes, without adequate reason, connecting it with cupressus. Another derivation is from cuprum, "copper," formerly found in the island; but the chalkos kuprios or aes cyprium probably took its name from the island, not the island from the metal.Cyprus is reckoned by Strabo (or Timaeus, whom he follows) to be the third in extent of the Mediterranean isles. Its shape was aptly compared by the ancients to the outspread skin of an ox, or to the fleece of a sheep. Its extreme length, from Cape Acamas (now Cape Arnaouti or Epiphanio) on the west to the promontory Dinaretum (now St. Andrea) on the east, is about 140 miles; its greatest breadth, from Crommyon (now Cormaciti) on the north to Cape Curias (now Cape Gatto), on the south, about 60; its width varying greatly, the long strip that ends at Dinaretum being very narrow and scarcely more than 10 miles across at any point. Off Dinaretum are several small islands called Kleides (Keys). The coast is provided with numerous bays; but the harbors are now mere roadsteads, though the remains of ancient artificial harbor moles are to be seen at several places (as New Paphos, Soli, etc.).

From Crommyon to Dinaretum, along and quite near the coast, extends a mountainous chain, of which the highest peaks are Buffavento (3240 ft.), Pentedactylon (2480 ft.), and Elias (2810 ft.). The principal ranges, however, are in the west and southwest, the highest point being Mount Olympus (Trodos or Troödos Tro, 6590 ft.), nearly midway between Curium on the south coast and Soli on the north, from the top of which a view of the whole island can be obtained. Next in height is Mount Adelphi (Maschera, 5380 ft.), a few miles to the east; still farther east, a hill (4370 ft.) whose ancient name is unknown; and still farther east again, Mount Santa Croce (Stavros, 2300 ft.). The chain extends nearly to Famagousta (Ammochostos, Constantia-Salamis), with frequent spurs to the shore; and spurs also extend from Olympus radially to the north, west, and south. Between the two ranges is a vast plain, now called the Messouria, whose principal river is the Pidias (Pidaeas), emptying into the sea near Salamis. The Messouria to-day is one vast grain-field, interspersed with insignificant villages. The island formerly abounded in trees and timber, of which it is now mostly denuded, though the kharub, olive, fig, orange, date-palm, lemon, nectarines, apricots, etc., and others suited to the climate flourish. Wild grape-vines still grow to an immense size. Wine, of various sorts, is abundant; the best and most famous being the Commanderia wine, so named from its original producers, the Knights of St. John, at Colossi. Formerly Cyprus yielded to no region in fertility, producing an abundance of grain, wine, oil, and fruits. At the proper season the hills and uncultivated plains are carpeted with anemones, ranunculuses, crocuses, hyacinths, squills, and a great variety of other flowers, especially those with bulbous roots. One ancient epithet of Cyprus is euôdês. But agriculture, along with irrigation and drainage, is much neglected. Salt lakes, or "Salines," exist near Larnaca, the ancient Citium, furnishing now, as in the times of Pliny , vast supplies of salt for home consumption and exportation, the salt coating the surface as the summer heat evaporates the water. The climate is still that of the ancient nimio calore.

Although the names of special historians have come down to us, we possess no ancient special treatise or history of the island, but are dependent for information anciently current upon the frequent mention in the Greek and Roman classics, with brief notices in the later historians. These are best collected in Engel's monograph Kypros (Berlin, 1841).

The earliest inhabitants have generally been supposed to be Poenicians, and it is true that the Phoenician language retained its hold in certain parts of Cyprus as late as anywhere, contemporarily, of course, with the Greek, the Lycian (locally), and later with the Latin. The Cypriotes, however, spoke a language peculiar to themselves, as was long ago evident from the scattered glosses preserved by the grammarians and lexicographers, and as has lately been further and most conclusively shown by the recent discovery and decipherment of inscriptions in the peculiar Cypriote character. This language was essentially Greek; and the Greek of Cyprus to-day embraces many peculiarities of its own. The legendary hero of Cyprus was Cinyras, who is said to have come to the island at the time of the beginning of the Trojan War. Without going into the matter of the legend, it may be said that Greek inscriptions of the "Cinyradae" (the priestly caste of Old Paphos, etc.) have been found in the island within the last twenty years.

The chief religion of the island was notoriously the worship of Venus; but with few exceptions (as e. g. Zeus Labranios, introduced near Amathus from Caria) the religion and deities were introduced from Phoenicia, and thus indirectly from the farther East--with, however, some Greek modification. Aphrodité, Apollo, Hercules, and other deities usually called Greek or Roman were thus introduced, the Greek and Phoenician names of some of them appearing now and then on the same bilingual inscription. Aphrodité had her epithet of "Paphian" not only at Paphos, where her rites included all the extravagancies of Mylitta at Babylon, but at the other seats of her worship--Golgos, Dali, Cerynia, etc. Apollo Hylates, who had a temple at Curium, is called by that name and also by his Phoenician name of Resheph Mical on a [p. 457] bilingual inscription found at Dali. A temple to Eshmunmelqarth (=Aesculapius-Hercules), a Phoenician deity much like the Greek Palaemon and the Roman Portumnus, near the Salines at Larnaca, has furnished a number of Phoenician inscriptions of the fourth century b.c.; while a temple to Artemis Paralia, close at hand, has furnished a few Greek inscriptions and an immense number of valuable terra-cotta remains.

Aside from the mythical reign of Cinyras over the whole island, the territory, so far as we know, was broken up into a number of kingdoms, whose detailed history has well-nigh perished. A dynasty of Phoenician kings ruled over Citium, Idalium, and Tamassus in the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. Salamis, said to have been founded by Teucer, and by him named after his native city, had its own Greek kings at the same period. Paphos had its dynasty of the Cinyradae, who seem also to have extended their power over Amathus and certain other parts. Soli and Cythrea traced their origin to the Athenians; Lapethus and Cerynia to a Lacedaemonian colony under Praxander and an Achaean one under Cepheus; Curium to the Argives. A town Asiné, whose site is not known, is said to have been colonized by the Dryopians; Neo-Paphos by Agapenor. The promontory Acamas is said to have its name from the hero of the Trojan War. Old Paphos, Amathus, and Citium were founded by the Phoenicians; and of these, Citium (with Dali and Tamassus) seems to have retained its Phoenician character with less modification than the others. Carpassia seems also to have had a Phoenician origin. Articles of Phoenician manufacture--bronze, gold, silver, pottery, etc.--have been found in abundance all over the island.

Aside from these scattered data, we know that Thothmes III. of Egypt (cir. B.C. 1500) conquered Cyprus; Belus of Tyre was at one time its master; ten kingdoms, including Soli, Chytri, Curium, Lapethus, Cerynia, Neo Paphos, Marium, Idalium, Citium, and Amathus, sent their submission to the Assyrian Esarhaddon (cir. B.C. 890); Sargon put the island to tribute (cir. B.C. 707); Apries (Pharaoh Hophra) of Egypt defeated some Cyprian monarchs near Citium, and returned home laden with their spoils; Amasis of Egypt overran the island and put it to tribute, but the Cyprian rulers joined Cambyses the Persian against the son of Amasis. The king of Amathus revolted from the Persians in the time of Darius, and the longest record extant in the Cypriote character commemorates one of the side issues of this struggle. In B.C. 477, the Athenians and Lacedaemonians conquered part of Cyprus from the Persians; and a war resulted in which the Greeks, with the Tyrians and Egyptians as allies, were on one side, and the Persians on the other. The power of Alexander the Great was both felt and helped in Cyprus, after which, under the Ptolemies, followed wars and doubtful sovereignty, till Demetrius Poliorcetes conquered the island (cir. B.C. 306). About B.C. 296, Ptolemy Soter took the island, after which it remained under Egypt till conquered by the Romans.

Literature and the arts flourished in Cyprus even from a very early period, as witness the "Cypria Carmina," by some attributed to Homer. Citium was the birthplace of Zeno. It is foreign to the present article to trace the history of the island during the Roman rule, the Arabs, the dukedoms of the Crusades, Richard of England, the Lusignans, the Turks, and the recent occupation by the English. Its geographical position made it the field for the exhibition of the arts, deeds, and cults of various nations; and its remains, as brought to light in the explorations of the last twenty-five [p. 458] years, have given a deeper insight into the ancient life and occupations and attainments of its successive peoples and masters than it had been thought possible hitherto to attain, and necessitated the rewriting of the principal chapters in the history of ancient art. From the time of Pococke, who, nearly three centuries ago, made his famous discoveries of Phoenician inscriptions (chiefly about Citium), down to the English occupation, scattered and partial explorations have been made. The discovery, in the first half of this century, of inscriptions in a character hitherto unknown, and their decipherment, from 1873 onward, has furnished most valuable clues to the history of religions in Cyprus and the transference of deities thither from the East, besides many minor historical matters and a vast addition to the knowledge of Greek dialects. The characters are syllabic, with peculiar laws of writing, and the language Greek. Some hundreds of these inscriptions are now known (the most of them found by Di Cesnola)--some bilingual (Phoenician and Cypriote) and some digraphic (Greek and Cypriote). The decipherment is a brilliant record--George Smith, of England, discovering the key in a bilingual inscription now in the British Museum; R. H. Lang simultaneously and independently proving the incorrectness of certain previous attempts by others; after which Samuel Birch made additional progress; and complete inscriptions were first read simultaneously and independently by Justus Siegismund and W. Deecke of Strassburg, M. Schmidt of Jena, and I. H. Hall of New York, since which time many writers have contributed lexicographic and dialectic additions.

The discoveries by exploration and excavation have been chiefly made (though the work of others is not inconsiderable) by L. P. di Cesnola, while U. S. Consul at Cyprus, from 1866 to 1877. His work covered nearly all parts of the island, discovering the sites of many ancient cities, and ruins of others whose ancient identity is not yet known, besides many temples, necropoles, ancient aqueducts, and other remains, including over 200 inscriptions, in Assyrian, Cypriote, Phoenician, Greek, and Latin. The greatest number (many thousands) and most important of the objects discovered are deposited in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, though many found their way to European museums and private collections. The statuary, pottery, terra-cottas, glass, gold, silver, and gems are a unique and unrivalled collection, and their value for the study of Phoenician and Greek archæology, art, and history appears in their unceasing use in the learned publications of all countries. Since the occupation of Cyprus by the English, others have excavated and explored, but by no means on the same scale, the principal works accomplished being the further excavation of the site of the greater temple of Venus at Old Paphos, and some large operations near Salamis.

For authorities, among many, see Engel, Kypros, above referred to; Di Cesnola, Cyprus (New York and London, 1878); R. H. Lang, Cyprus, etc. (London, 1878). The literature in periodicals and minor volumes is very extensive. (Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1898)