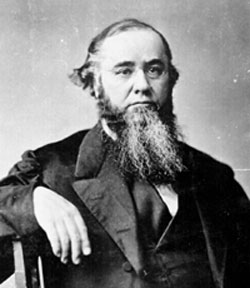

Edwin McMasters Stanton (1814-1869)

Edwin McMasters Stanton (December 19, 1814 - December 24, 1869), was an American lawyer, politician and Secretary of War through most of the American Civil War and in the Reconstruction era.

Stanton was born in Steubenville, Ohio, the eldest of the four children of David and Luvy (Norman) Stanton, devout Methodist parents. His father was a physician of Quaker stock. Beginning in childhood, he suffered from asthma throughout his life. After graduating from Kenyon College in 1833, he studied law under a judge. He was admitted to the Ohio bar in 1835, but had to wait several months until his 21st birthday before he could begin to practice. He practiced law in Steubenville until 1847, when he moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

In 1856 Stanton moved to Washington, D.C., where he had a large practice before the federal courts and the Supreme Court. During all these years Stanton remained a staunch Democrat but grew steadily more outspoken in support of antislavery measures.

Stanton was born in Steubenville, Ohio, the eldest of the four children of David and Luvy (Norman) Stanton, devout Methodist parents. His father was a physician of Quaker stock. Beginning in childhood, he suffered from asthma throughout his life. After graduating from Kenyon College in 1833, he studied law under a judge. He was admitted to the Ohio bar in 1835, but had to wait several months until his 21st birthday before he could begin to practice. He practiced law in Steubenville until 1847, when he moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

In 1856 Stanton moved to Washington, D.C., where he had a large practice before the federal courts and the Supreme Court. During all these years Stanton remained a staunch Democrat but grew steadily more outspoken in support of antislavery measures.

While in Ohio, Stanton became active in the local antislavery society and was elected Prosecuting Attorney of Harrison county as a Democrat. In 1857, he was appointed by U.S. Attorney General Jeremiah Black to represent the federal government in California land cases. Two years later, he was one of the lead attorneys on the defense team of Congressman and later Union General Daniel Sickles. Sickles was tried on a charge of murdering his wife's lover (Philip Barton Key, son of Francis Scott Key), but was acquitted after Stanton invoked the first use of the insanity defense in U.S. history.

After the 1860 presidential election, Stanton gave up a lucrative law practice to become Attorney General in the lame-duck presidential administration of James Buchanan. He advised Buchanan to act forcefully against the South, but when the president did not, Stanton clandestinely keep the Republicans, particularly William Henry Seward, informed about White House policy decisions. Stanton was politically opposed to Republican Abraham Lincoln in 1860 and referred to him as the "original gorilla". After Lincoln was elected president, Stanton agreed to work as a legal adviser to the inefficient Secretary of War, Simon Cameron.

In 1862, President Lincoln decided to remove the corrupt and ineffective Secretary of War, Simon Cameron, by appointing him Minister to Russia. Seward and Salmon Chase successfully lobbied the President to name Stanton as his new Secretary of War on January 15, 1862. He once again gave up a prosperous law practice to enter public service. He accepted the position only to "to help save the country." He was a very effective in administering the huge War Department, but he devoted considerable amounts of his energy to the persecution of Union officers whom he suspected of having traitorous sympathies for the South and the Civil War was a time of great political intrigue within the U.S. Army. The president recognized Stanton's ability, but whenever necessary Lincoln managed to "plow around him." When pressure was exerted to remove the unpopular secretary from office, Lincoln replied, "If you will find another secretary of war like him, I will gladly appoint him." During this period Stanton's opinion of Lincoln changed. At Lincoln's death Stanton said "there lies the most perfect ruler of men the world has ever seen." He proved to be a strong and effective cabinet officer, instituting practices to rid the War Department of waste and corruption.

When Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney died in October 1864, Stanton wanted to be named as his replacement. Lincoln believed, though, that he was more important to the Union cause as Secretary of War, so the President appointed Chase, instead.

After the assassination of Lincoln (April 1865), Stanton uttered the memorable line, "Now he belongs to the ages." He played a leading role in the investigation and trial of the conspirators, and for a short time he virtually directed the conduct of government in the stricken capital.

It was Stanton who was at the center of the battle to impeach and remove President Andrew Johnson from office. After Lincoln's assassination, Stanton had continued to serve as Johnson's Secretary of War. However, he became vehemently opposed to Johnson's lenient Reconstruction policies, and consequently worked with Republicans to implement Congressional Reconstruction in the South. After first suspending Stanton in August 1867, Johnson fired the Secretary in February 1868. Stanton refused to leave office, claiming job protection under the Tenure of Office Act, passed by the Radicals in Congress (1867) over the president's veto. He locked himself in the War Department until the Senate voted against the President's removal. When the Senate vote fell one short of conviction, Stanton had no alternative but to surrender his office (May 26, 1868) and return to private law practice.

Stanton's wish to sit on the Supreme Court appeared to be fulfilled when President Grant appointed him and the Senate confirmed him on the same day, December 20, 1868. He died, however, four days later in Washington, D.C. and is buried there in Oak Hill Cemetery.

Stanton was born in Steubenville, Ohio, the eldest of the four children of David and Luvy (Norman) Stanton, devout Methodist parents. His father was a physician of Quaker stock. Beginning in childhood, he suffered from asthma throughout his life. After graduating from Kenyon College in 1833, he studied law under a judge. He was admitted to the Ohio bar in 1835, but had to wait several months until his 21st birthday before he could begin to practice. He practiced law in Steubenville until 1847, when he moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

In 1856 Stanton moved to Washington, D.C., where he had a large practice before the federal courts and the Supreme Court. During all these years Stanton remained a staunch Democrat but grew steadily more outspoken in support of antislavery measures.

Stanton was born in Steubenville, Ohio, the eldest of the four children of David and Luvy (Norman) Stanton, devout Methodist parents. His father was a physician of Quaker stock. Beginning in childhood, he suffered from asthma throughout his life. After graduating from Kenyon College in 1833, he studied law under a judge. He was admitted to the Ohio bar in 1835, but had to wait several months until his 21st birthday before he could begin to practice. He practiced law in Steubenville until 1847, when he moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

In 1856 Stanton moved to Washington, D.C., where he had a large practice before the federal courts and the Supreme Court. During all these years Stanton remained a staunch Democrat but grew steadily more outspoken in support of antislavery measures.