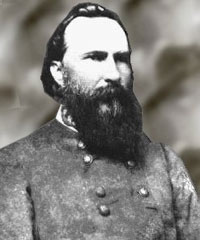

James Longstreet (1821-1904)

James Longstreet (January 8, 1821 - January 2, 1904) was one of the foremost generals of the American Civil War, and later enjoyed a successful post-war career working for the government of his former enemies, as a diplomat and administrator.

Early Life

Longstreet was born in Edgefield District, South Carolina, the son of a farmer, but grew up in Augusta, Georgia, until age 12 when his father died and the family moved to Somerville, Alabama. He was appointed to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point by the state of Alabama in 1838 and graduated in 1842. He served with distinction in the Mexican War, was wounded at Chapultepec, and received two brevets and the staff rank of major. He resigned from the U.S. Army on June 1, 1861 to cast his lot with the Confederacy in the Civil War.

Longstreet was born in Edgefield District, South Carolina, the son of a farmer, but grew up in Augusta, Georgia, until age 12 when his father died and the family moved to Somerville, Alabama. He was appointed to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point by the state of Alabama in 1838 and graduated in 1842. He served with distinction in the Mexican War, was wounded at Chapultepec, and received two brevets and the staff rank of major. He resigned from the U.S. Army on June 1, 1861 to cast his lot with the Confederacy in the Civil War.

Career as Confederate General

Longstreet was already highly regarded as an officer, and he was almost immediately appointed as a brigadier general in the Confederate Army. His assignments included: brigadier general, CSA June 17, 1861); commanding brigade (in 1st Corps after July 20), Army of the Potomac July 2 - October 7, 186 1); major general, CSA (October 7, 1861); commanding division, Ist Corps, Army of the Potomac (October 14-22, 1861); commanding division (in Potomac District until March 1862), Department of Northern Virginia (October 22, 1861 - July 1862); commanding lst Corps, Army of Northern Virginia July 1862 - February 25, 1863; May - September 9, 1863; April 12 - May 6, 1864; and October 19, 1864-April 9, 1865); lieutenant general, CSA (October 9, 1862); commanding Department of Virginia and North Carolina (February 25-May 1863); commanding his corps, Army of Tennessee (September 19-November 5, 1863); and commanding Department of East Tennessee (November 5, 1863-April 12, 1864).

Commanding a brigade, he fought well at the First Battle of Bull Run, and earned a promotion to major general.

During the Peninsula Campaign in the spring and summer of 1862 he saw further action at Yorktown, Williamsburg, Seven Pines, and the Seven Days. In the final days of the latter he also directed A.P. Hill's men. Longstreet's career took off when Gen. Robert E. Lee took command of the Army of Northern Virginia. During the Seven Days Battles, Longstreet had operational command of nearly half the Lee's army.

As a general, Longstreet showed a talent for defensive fighting, preferring to position his troops in strong defensive positions and compel the enemy to attack him. Once the enemy had worn itself down, then and only then would Longstreet contemplate an attack of his own. In fact, troops under his command never lost a defensive position during the war. Lee referred to Longstreet affectionately as his Old War Horse. (Longstreet's friends generally called him Pete.) His record as an offensive tactician was mixed, however, and he often clashed with the highly aggressive Lee on the subject of the proper tactics to employ in battle.

Ironically, one of his finest hours came in August 1862, when he commanded what had become known as the First Corps at the Second Battle of Bull Run. Here, he and his counterpart in command of the Second Corps, Lieut. Gen. Thomas J. Jackson, switched their normal roles, with Jackson fighting defensively on the Confederate left, and Longstreet delivering a devastating flank attack on the right that crushed the slightly larger Union Army of Virginia.

The next month, at the Battle of Antietam, Longstreet held his part of the Confederate line against Union forces twice as numerous. On October 9, a few weeks after Antietam, Longstreet was promoted to lieutenant general, the senior Confederate officer of that rank.

He only enhanced his reputation that December, when his First Corps played the decisive role in the Battle of Fredericksburg. There, Longstreet positioned his men behind a stone wall and held off fourteen assaults by Union forces. About 10,000 Union soldiers fell; Longstreet's men lost but 500.

In the winter and early spring of 1863, Longstreet bottled up Union forces in the city of Suffolk, Virginia, a minor operation but one that was very important to Lee's army, still stationed in devastated central Virginia. By conducting a siege of Suffolk, Longstreet enabled Confederate authorities to collect huge amounts of food—food that had been under Union control—and send it to feed Lee's hungry soldiers. However, this operation caused Longstreet and 15,000 men of the First Corps to be absent from the Battle of Chancellorsville in May.

Longstreet rejoined Lee's army after Chancellorsville and took part in Lee's Gettysburg campaign, where he clashed with Lee about the tactics Lee was using. Longstreet, who had come to believe in the strategic offense and the tactical defense, was proven right when the Confederate attacks on the second and third days were repulsed. This campaign marked a fundamental change in the way Longstreet was employed by Lee. In the past, Lee had preferred to use Longstreet in defensive roles, which were his strength, and use Jackson and the Second Corps to spearhead his attacks. But Jackson had been killed at Chancellorsville, and now Lee wanted Longstreet—his best remaining lieutenant—to fill that role.

Longstreet was willing and capable of doing so, but he argued with Lee a number of times during the battle of Gettysburg, essentially telling Lee that his tactics were going to lead to defeat. Longstreet advocated disengagement from the enemy after the first day's battle, embarking on a strategic flanking movement to place themselves on the Union line of communication, and inviting a Union attack. He argued that Lee had agreed before the campaign that this "strategic offensive, tactical defensive" would be the proper course. But Lee had settled on the tactical offensive. On July 2, the second day of the battle, Longstreet's assault on the Union left nearly succeeded, but on July 3, when Lee ordered Longstreet, against his wishes, to attack the Union center in what became known as "Pickett's Charge", the Confederates lost 7,000 men in an hour. Longstreet was right, and Lee was wrong and immediately admitted as much, but to many of Lee's admirers, such as Jubal Early and the Lost Cause advocates after the war, the lost battle was Longstreet's fault.

Lee never blamed anyone but himself for the defeat, and in fact dispatched Longstreet to Georgia that fall in response to a desperate appeal for help from the Confederate Army of Tennessee. That resulted in Longstreet and 14,000 of his First Corps veterans taking part in the Battle of Chickamauga that September. Longstreet led an attack of his men and some of the Army of Tennessee men that routed the Union Army of the Cumberland and won the greatest Confederate victory ever in the western theatre.

Longstreet soon clashed with the much maligned Army of Tennessee commander, Gen. Braxton Bragg, when Bragg failed to capitalize on the victory by finishing off the Union army and recapturing the city of Chattanooga, Tennessee. Longstreet became leader of a group of senior commanders of the army who conspired to have Bragg removed. The situation became so grave that Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederacy, was forced to intercede in person. What followed was one of the most bizarre scenes of the war, with Bragg sitting red faced as a procession of his commanders declared him incompetent. Amazingly, Davis sided with Bragg and did nothing to resolve the conflict. Bragg not only stayed in command, he sent Longstreet and his men on a disastrous campaign into east Tennessee, where in December, they were defeated in an attempt to recapture the city of Knoxville. After Bragg was driven back into Georgia, Longstreet and his men returned to Lee.

Longstreet helped save the Confederate Army from defeat in his first battle back with Lee's army, the Battle of the Wilderness in May, 1864, where he launched a powerful flanking attack against the Union II Corps and nearly drove it from the field. But he was wounded in the process—accidentally shot by his own men not a mile away from the place where Jackson befell the same fate a year earlier—and missed the rest of the 1864 spring campaign, where Lee sorely missed his skill in handling the army. He rejoined Lee from October, 1864, to March, 1865, during the Siege of Petersburg, commanding the defenses in front of the capital of Richmond. He surrendered with Lee at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865.

After the War

After the war, Longstreet renewed his friendship with his old friend and adversary, Lieut. Gen. and future President Ulysses S. Grant, and became the only major Confederate officer to join the postwar Republican party. For this, he lost favor with many Southerners, but nevertheless enjoyed a successful second career. He also converted to Catholicism when he married his second wife which also made him less popular in the more Protestant South. Moreover he advised the Southern state governments to extend civil and voting rights to freed slaves, much to the chagrin of his former Confederate comrades.

Longstreet decided to make New Orleans his first post-War home. He found various business opportunities there, associating himself with a cotton brokerage and soon assumed the presidency of the Great Southern and Western Fire, Marine and Accident Insurance Company. He unsuccessfully sought the presidency of the Mobile and Ohio Railroad but was made president of the Southern Hospital Association.

Ulysses S. Grant appointed Longstreet to the position of surveyor of customs for the port of New Orleans after he was inaugurated President in 1869. In June 1873 he was named to the four-year position on the Levee Commission of Engineers. By 1878 Rutherford B. Hayes had appointed him deputy collector of internal revenue. He remained in the position for only a few months, before accepting the position of postmaster in Gainesville, Georgia.

In May 1880, President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed Longstreet as his ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. President Garfield, another former Union general, nominated him to a four-year term as U.S. Marshall for Georgia, a position he had long desired. He served in that capacity for slightly over three years, but his tenure was plagued by controversy and political intrigue.

With the election of President Grover Cleveland Longstreet had no prospects of receiving another position and he went into semi-retirement in Gainesville, Georgia. There he operated the Piedmont Hotel, and enjoyed raising turkeys, tending an orchard, and nurturing his vineyard. His wife, Louise died in December of 1889. He began to write his memoirs, but the task was to take five years.

Longstreet married Helen Dortch in September of 1897. She was a native Georgian and assistant state librarian at the time of the marriage, and only 34 years old.

Longstreet served from 1897 to 1904, under Presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt, as U.S. Commissioner of Railroads.

Late in life, after bearing criticism of his war record from other Confederates for decades, he refuted most of their arguments in his memoirs entitled From Manassas to Appomattox. The memoir was published in 1896 and created a furor of controversy, which continues today in Civil War circles

He attended many military and Civil War related reunions, including the 100th Anniversary of the U.S. Military Academy in 1902 and the Memorial Day Parade of 1902, when he commented "I hope to live long enough to see my surviving comrades march side by side with the Union veterans along Pennsylvania Avenue, and then I will die happy."

He outlived most of his detractors and died of pneumonia on the morning of January 2, 1904, while visiting his daughter's home in Gainesville, Georgia, just six days short of his 83rd birthday. He is buried in Alta Vista Cemetery.

Because of criticism from authors in the Lost Cause movement (Jubal Early in particular), Longstreet's war career was disparaged for many years after his death. The publication of Michael Shaara's novel The Killer Angels in 1974, based in part on Longstreet's memoirs, has been credited with restoring his reputation as an outstanding general.

In 1990, one of the last monuments erected at Gettysburg National Military Park is a belated tribute to Longstreet. He is depicted on his horse at ground level in a grove of trees in Pitzer Woods, unlike most generals, who are elevated on tall bases overlooking the battlefield. This is indicative of the continuing controversies over the career of James Longstreet.

Longstreet was born in Edgefield District, South Carolina, the son of a farmer, but grew up in Augusta, Georgia, until age 12 when his father died and the family moved to Somerville, Alabama. He was appointed to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point by the state of Alabama in 1838 and graduated in 1842. He served with distinction in the Mexican War, was wounded at Chapultepec, and received two brevets and the staff rank of major. He resigned from the U.S. Army on June 1, 1861 to cast his lot with the Confederacy in the Civil War.

Longstreet was born in Edgefield District, South Carolina, the son of a farmer, but grew up in Augusta, Georgia, until age 12 when his father died and the family moved to Somerville, Alabama. He was appointed to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point by the state of Alabama in 1838 and graduated in 1842. He served with distinction in the Mexican War, was wounded at Chapultepec, and received two brevets and the staff rank of major. He resigned from the U.S. Army on June 1, 1861 to cast his lot with the Confederacy in the Civil War.