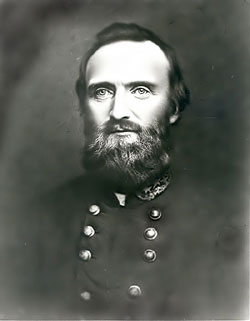

Thomas Jonathan Jackson (1824-1863)

Confederate general in the American Civil War (born Jan. 21, 1824, Clarksburg, Va. [now in W.Va.], U.S.; died May 10, 1863, Guinea Station [now Guinea], Va.) one of its most skillful tacticians, who gained his sobriquet "Stonewall" by his stand at the First Battle of Bull Run (called First Manassas by the South) in 1861.

Early life and career.

Thomas Jonathan Jackson was the third child of Julia Neale Jackson (1789-1831) and Jonathan Jackson (1790-1826), an attorney. Both of Jackson's parents were natives of Virginia. The family already had two young children and were living in Clarksburg, in what is now West Virginia, when Thomas, their third son, was born.

Two years later, tragedy struck the family when Jackson's father and sister Elizabeth (age six) died of typhoid fever. Jackson's mother gave birth to Thomas' sister Laura Ann the next day. Julia Jackson was widowed at 28 and was left with much debt, selling all the family's possessions to pay them. She declined family charity and moved into a small one-room house. Julia took in sewing and taught school to support herself and her three young children for about four years. In 1830, she remarried, but her new husband, also an attorney, did not like his stepchildren, and there were continuing financial problems. Then, after giving birth to Thomas' half-brother, she died of complications, leaving her three children orphaned. Julia was buried in an unmarked grave in a homemade coffin in a small town along the James River and Kanawha Turnpike in Fayette County.

Thomas Jonathan Jackson was the third child of Julia Neale Jackson (1789-1831) and Jonathan Jackson (1790-1826), an attorney. Both of Jackson's parents were natives of Virginia. The family already had two young children and were living in Clarksburg, in what is now West Virginia, when Thomas, their third son, was born.

Two years later, tragedy struck the family when Jackson's father and sister Elizabeth (age six) died of typhoid fever. Jackson's mother gave birth to Thomas' sister Laura Ann the next day. Julia Jackson was widowed at 28 and was left with much debt, selling all the family's possessions to pay them. She declined family charity and moved into a small one-room house. Julia took in sewing and taught school to support herself and her three young children for about four years. In 1830, she remarried, but her new husband, also an attorney, did not like his stepchildren, and there were continuing financial problems. Then, after giving birth to Thomas' half-brother, she died of complications, leaving her three children orphaned. Julia was buried in an unmarked grave in a homemade coffin in a small town along the James River and Kanawha Turnpike in Fayette County.

Jackson was seven when his mother died, and he and his sister Laura Ann were sent to live with their paternal uncle, Cummins Jackson, who owned a grist mill in Jackson's Mill (near present-day Weston). Cummins Jackson was strict to Thomas Jackson, often giving his own views on things. Thomas Jackson looked up to Cummins as a schoolteacher. Their older brother, Warren, went to live with other relatives on his mother's side of the family, but he died of tuberculosis in 1841 at the age of 20. Jackson helped around his uncle's farm, tending sheep with the assistance of a sheepdog, driving teams of oxen and helping harvest the fields of wheat and corn. Formal education was not easily obtained, but he attended school when and where he could. Much of Jackson's education was self-taught. He would often sit up at night reading by the flickering light of burning pine knots. The story is told that Thomas once made a deal with one of his uncle's slaves to provide him with pine knots in exchange for reading lessons. This was in violation of a law in Virginia at that time that forbade teaching a slave to read or write, but nevertheless, Jackson taught the man as promised. In his later years at Jackson's Mill, Thomas was a schoolteacher.

Jackson had little opportunity for formal education in his early years, but he received an appointment, in 1842, to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Because of his inadequate schooling, he had difficulty with the entrance examinations. As a student, he had to work several times harder than most cadets to absorb lessons. However, displaying a dogged determination that was to characterize his life, he became one of the hardest working cadets in the academy. Thomas Jackson graduated 17th out of 59 students in the Class of 1846 and was commissioned as a second lieutenant assigned to artillery.

Young Lieutenant Jackson began his U.S. Army career in the First Artillery Regiment. He joined his regiment in Mexico, where the United States was then at war. In the Mexican War he first met General Robert E. Lee, who later became the commanding general of the Confederate armies, and it was here that Jackson first exhibited the qualities for which he later became famous: resourcefulness, the ability to keep his head, and bravery in the face of enemy fire. When he refused what he felt was a "bad order", to withdraw his troops, he was confronted by another superior. He explained his rationale, and claimed that, with only 50 more troops, he could persevere and win the particular situation. He served at Veracruz, Contreras, Chapultepec, and Mexico City, eventually earning two brevets. At the end of the fighting in Mexico, having been promoted to first lieutenant and to the brevet rank of major, he was assigned to the occupation forces in Mexico City.

Finding service in the peacetime army tedious, he resigned his commission in the spring of 1851, and accepted a newly created position to teach at the Virginia Military Institute (VMI), in Lexington, Virginia. He became Professor of Natural and Experimental Philosophy and Instructor of Artillery. Jackson's teachings are still used at VMI today because they are military essentials that are timeless, to wit: discipline, mobility, assessing the enemy's strength and intentions while attempting to secret your own, and the efficacy of artillery combined with infantry in a literal combined attack. However, despite the quality of his work, he was not popular as a teacher. The students mocked his apparently stern, religious nature and his eccentric traits. Little as he was known to the white inhabitants of Lexington, he was revered by the slaves, to whom he showed uniform kindness, and for whose moral instruction he worked unceasingly. During this time Jackson even began a Sunday school for blacks, both slave and free. Though he worked hard at his new duties, he never became a popular or highly successful teacher. A stern and shy man, he earned a reputation for eccentricity that followed him to the end of his career. His strong sense of duty and moral righteousness, coupled with great devotion to the education of cadets, earned for him the derisive title "Deacon Jackson" and comparison with Oliver Cromwell.

While an instructor at VMI, in 1853, Thomas Jackson married Elinor "Ellie" Junkin, whose father was president of Washington College in Lexington. A son was born to them but unfortunately, Ellie died during childbirth and the newborn child died immediately following the birth.

After a tour of Europe, in 1857, Jackson married again. Mary Anna Morrison was from North Carolina, where her father was the first president of Davidson University. They had a daughter named Mary Graham on April 30, 1858, but the baby died less than a month later. Another daughter was born in 1862, shortly before her famous father's death. The Jacksons named her Julia Laura, after his mother and sister.

In November 1859, at the request of the governor of Virginia, Major William Gilham led a contingent of the VMI Cadet Corps to Charles Town to provide an additional military presence at the execution by hanging on December 2, 1859 of militant abolitionist John Brown following his raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry. Major Jackson was placed in command of the artillery, consisting of two howitzers manned by 21 cadets.

Upon the outbreak of the Civil War he offered his services to his state of Virginia and was ordered to bring his VMI cadets from Lexington to Richmond. Soon after, he received a commission as colonel in the state forces of Virginia and was charged with organizing volunteers into an effective Confederate army brigade, a feat that rapidly gained him fame and promotion. He was eventually given command of a brigade. On April 27, 1861, Virginia Governor John Letcher ordered Colonel Jackson to take command at Harpers Ferry, where the Shenandoah River flows into the Potomac. His mission was to fortify the area and hold it if possible. There he assembled the famous "Stonewall Brigade". The fabled brigade included the 2nd, 4th, 5th, 27th, and 33rd Virginia infantry regiments. All of these units were from the Shenandoah Valley region of Virginia. Jackson's first assignment in the Confederate cause was the small command at Harpers Ferry, Va. (now West Virginia),

During the charge that took place at Harpers Ferry, Colonel Jackson jumped in front of a soldier who was about to be killed by a sword thrust and killed the man that was attacking the soldier. After the Battle of Harpers Ferry, because of his bravery, he was promoted to brigadier general. When General Joseph E. Johnston took over the Confederate forces in the valley, with Jackson commanding one of the brigades, Jackson withdrew to a more defensible position at Winchester.

Battle of Manassas.

Jackson rose to prominence and earned his nickname after the first battle of Bull Run (known as the First Battle of Manassas in the South). In July 1861 the invasion of Virginia by Federal army troops began, and Jackson's brigade moved with others of Johnston's army to unite with General P.G.T. Beauregard on the field of Bull Run in time to meet the advance of General Irvin McDowell's Federal army. It was here that he stationed his brigade in a strong line and Brigadier General Barnard E. Bee exhorted his own troops to reform by shouting, "There stands Jackson like a stone wall. Rally behind the Virginians!" Jackson was quickly promoted to divisional command.

The spring of 1862 found Jackson again in the Shenandoah Valley, where his diversionary tactics prevented reinforcements being sent to Federal army general George B. McClellan, who was waging the peninsular campaign against Richmond, the Confederate capital. Jackson's strategy possibly accounted for Lee's victory later in the Seven Days' Battles. Lee, then chief military adviser to Confederate president Jefferson Davis, suggested to Jackson that he use his troops to attack Federal troops in the valley and thus threaten Washington. He soundly thrashed the Union forces by a combination of great audacity, excellent knowledge and shrewd use of the terrain, added to the ability to inspire his troops to great feats of marching and fighting. With fewer than 17,000 men, he defeated 60,000 Union troops through a series of lightning marches and brilliant battles. Stonewall Jackson's reputation for moving his troops earned them the description of "foot cavalry". By rapid movement, Jackson closed separately with several Federal units and defeated them. In April he struck in the mountains of western Virginia; then on May 24-25 he turned on General Nathaniel P. Banks and drove him out of Winchester and back to the Potomac River.

He then quickly turned his attention to the southern end of the valley, defeating the Federals at Cross Keys, Va., on June 8, and at Port Republic on the next day.

In the spring of 1862, McClellan led the Peninsula Campaign, a major Union advance from Hampton Roads at Fort Monroe up the Virginia Peninsula between the York and James Rivers. Union forces reached the defenses of Richmond on June 1. After the campaign in the Shenandoah Valley ended in mid-June, Jackson and his troops were called to Richmond, Virginia to help there. By utilizing a railroad tunnel under the Blue Ridge Mountains he knew of which had been engineered and built by VMI founder Claudius Crozet, and then transporting troops to Hanover County on the Virginia Central Railroad, Jackson and his forces made a surprise appearance in front of McClellan at Mechanicsville. Reports had last placed Jackson's forces in the Valley, and their presence near Richmond added greatly to the Union commander's overestimation of the strength and numbers of the forces before him. This proved a crucial factor in McClellan's decision to retreat toward the James River. But Jackson arrived a day late, and his reputation lost some of its lustre, possibly because of his lack of experience in large-scale action; nevertheless, McClellan was beaten back and was ordered to evacuate the peninsula.

Jackson's troops served well under Robert E. Lee in the series of battles known as the Seven Days Battles, but Jackson's own performance in those battles is generally considered to be lackluster. The reasons are disputed, although a severe lack of sleep after the grueling march and railroad trip from the Shenandoah Valley was probably a large factor. Both Jackson and his troops were completely exhausted.

Jackson was now a corps commander under Lee. At the Second Battle of Bull Run (or the Second Battle of Manassas in the South), he helped to administer the Federals under Pope another defeat on the same ground as in 1861. Lee sent Jackson, by a wide encircling movement, to attack the rear of Pope's forces and bring on the Second Battle of Bull Run, in which Pope was soundly beaten.

Lee next crossed the Potomac for the "liberation" of Maryland. To protect Richmond, Lee detached Jackson to capture Harpers Ferry, which he did in time (September 13-15) to rejoin Lee at Antietam. The Confederate forces held their position, but the battle had been extremely bloody for both sides, and Lee took the Army of Northern Virginia back across the Potomac River, ending the invasion.

After his return to Virginia, Lee divided his army into two corps, General James Longstreet commanding the first and Jackson, now a lieutenant general, the second. At Fredericksburg, Va., in December, Jackson was in command of the Confederate right when Federal general Ambrose E. Burnside's rash attack was easily repulsed and he was crushingly defeated.

Death.

In April, General Joseph Hooker, Burnside's successor, attempted to turn the Confederate position on the Rappahannock River, south of Washington. There the seemingly invincible team of Lee and Jackson made its boldest move. Leaving a small detachment to meet Federal troops on the Rappahannock, Lee moved his main body, including Jackson's corps, to meet Hooker's threatened envelopment in the woods of Chancellorsville. He then divided his army again, keeping only 10,000 men to demonstrate against Hooker's front, and he sent Jackson to move secretly around Hooker's right with his entire corps.

The maneuver was completely successful. On the evening of May 2, Jackson rolled up the flank of the unsuspecting Federal forces. Then, in the moment of victory, tragedy struck. Jackson and his staff, who had ridden forward to organize the pursuit, were mistaken for a Union cavalry force by Confederate troops and fired upon. Jackson was hit by three bullets; his left arm had to be amputated by Dr. Hunter McGuire, and he died seven days later of pneumonia. Jackson's dying words: "Let us cross the river and rest in the shade of the trees". Upon hearing of Jackson's death, Robert E. Lee mourned the loss of both a friend and a trusted commander. The night Lee learned of Jackson's death, he told his cook, "William, I have lost my right arm" (deliberately in contrast to Jackson's left arm) and "I'm bleeding at the heart".

Legacy.

That Jackson was the ablest of General Robert E. Lee's generals is rarely questioned. The qualities of the two men complemented each other, and Jackson cooperated most effectively. In him were combined a deep religious fervour and a fiercely aggressive fighting spirit. He was a stern disciplinarian, but his subordinates and his men trusted him and fought well under his leadership. A master of rapid movement and surprise tactics, he kept his intentions sometimes so veiled in secrecy that often his own officers did not fully know his plans until they were ordered to strike.

Jackson is considered one of the great characters of the Civil War. He was profoundly religious, a deacon in the Presbyterian Church. He disliked fighting on Sunday, though that did not stop him from doing so. He loved his wife very much and sent her tender letters. He generally wore old, worn-out clothes rather than a fancy uniform, and often looked more like a moth-eaten private than a corps commander. He was also known to regularly chew lemons during marches, a taste for which he had acquired during his time in Mexico. In command Jackson was extremely secretive about his plans and extremely punctilious about military discipline.

The South mourned his death; he was greatly admired there. Many theorists through the years have postulated that if Jackson had lived, Lee might have prevailed at Gettysburg. Certainly Jackson's iron discipline and brilliant tactical sense were sorely missed, and might well have carried an extremely close fought battle.

He is buried at Lexington, Virginia, near VMI, in the Stonewall Jackson Memorial Cemetery. He is memorialized on Georgia's Stone Mountain, in Richmond on historic Monument Avenue, and in many other places.

After the War, his wife and young daughter Julia moved from Lexington to North Carolina. Mary Anna Jackson wrote two books about her husband's life, including some of his letters. She never remarried, and was known as the "Widow of the Confederacy", living until 1915. His daughter Julia married, and bore children, but she died of typhoid fever at the age of 26 years. A former Confederate soldier who admired Jackson, Captain Thomas R. Ranson of Staunton, Virginia, also remembered the tragic life of Jackson's mother. He went to the tiny mountain hamlet of Ansted in Fayette County, West Virginia, and had a marble marker placed over the unmarked grave of Julia Neale Jackson in Westlake Cemetery, to make sure that the site was not lost forever.

West Virginia's Stonewall Jackson State Park is named in his honor. Nearby, at Stonewall Jackson's historical childhood home, his Uncle's grist mill is the centerpiece of a historical site at the Jackson's Mill Center for Lifelong Learning and State 4-H Camp. The facility, located near Weston, serves as a special campus for West Virginia University and the WVU Extension Service.

The United States Navy submarine U.S.S. Stonewall Jackson (SSBN 634), commissioned in 1964, was named for Lieutenant General Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson. The words "Strength—Mobility" are emblazoned on the ship's banner. The words are taken from letters written by General Jackson, and were said to apply to the Polaris submarine as well as to the tactics he used so successfully. The submarine was decommissioned in 1995.

Thomas Jonathan Jackson was the third child of Julia Neale Jackson (1789-1831) and Jonathan Jackson (1790-1826), an attorney. Both of Jackson's parents were natives of Virginia. The family already had two young children and were living in Clarksburg, in what is now West Virginia, when Thomas, their third son, was born.

Two years later, tragedy struck the family when Jackson's father and sister Elizabeth (age six) died of typhoid fever. Jackson's mother gave birth to Thomas' sister Laura Ann the next day. Julia Jackson was widowed at 28 and was left with much debt, selling all the family's possessions to pay them. She declined family charity and moved into a small one-room house. Julia took in sewing and taught school to support herself and her three young children for about four years. In 1830, she remarried, but her new husband, also an attorney, did not like his stepchildren, and there were continuing financial problems. Then, after giving birth to Thomas' half-brother, she died of complications, leaving her three children orphaned. Julia was buried in an unmarked grave in a homemade coffin in a small town along the James River and Kanawha Turnpike in Fayette County.

Thomas Jonathan Jackson was the third child of Julia Neale Jackson (1789-1831) and Jonathan Jackson (1790-1826), an attorney. Both of Jackson's parents were natives of Virginia. The family already had two young children and were living in Clarksburg, in what is now West Virginia, when Thomas, their third son, was born.

Two years later, tragedy struck the family when Jackson's father and sister Elizabeth (age six) died of typhoid fever. Jackson's mother gave birth to Thomas' sister Laura Ann the next day. Julia Jackson was widowed at 28 and was left with much debt, selling all the family's possessions to pay them. She declined family charity and moved into a small one-room house. Julia took in sewing and taught school to support herself and her three young children for about four years. In 1830, she remarried, but her new husband, also an attorney, did not like his stepchildren, and there were continuing financial problems. Then, after giving birth to Thomas' half-brother, she died of complications, leaving her three children orphaned. Julia was buried in an unmarked grave in a homemade coffin in a small town along the James River and Kanawha Turnpike in Fayette County.