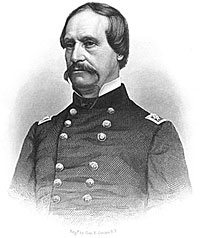

David Hunter (1802-1866)

David Hunter was born on July 21, 1802, in Washington, D.C. His father was a minister from Virginia who had served in the Revolutionary War, and his maternal grandfather was a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

Hunter graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., in 1822 and was assigned to frontier duty at Fort Dearborn, Illinois. He resigned in 1836 and spent six years in real estate before returning to the army as paymaster with the rank of major. He served as Major Paymaster during the Mexican War. A Whig turned Democrat and a one-time Chicago businessman, he was a professional soldier before the Civil War but because he served as a paymaster, lacked real military experience.

Hunter graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., in 1822 and was assigned to frontier duty at Fort Dearborn, Illinois. He resigned in 1836 and spent six years in real estate before returning to the army as paymaster with the rank of major. He served as Major Paymaster during the Mexican War. A Whig turned Democrat and a one-time Chicago businessman, he was a professional soldier before the Civil War but because he served as a paymaster, lacked real military experience.

Hunter had the good sense to seize political opportunities and take advantage of political connections. In 1860, stationed at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, Hunter began a correspondence with Lincoln that led to his being of the President's escorts on the trip to Washington, D.C. in 1861 and to his appointment in command of the militia protecting the new president. His actual military career was undistinguished. Upon arrival in Washington in 1861, he sought to command the city's defenses; instead, he was briefly appointed to take charge of the security of the White House. He worked with Cassius Clay and Kansas Senator James H. Lane to organize volunteer militia companies to protect the Executive mansion. For a few days, they bedded down in the White House East Room.

Despite his lack of combat experience, Hunter had served in the army for thirty years; he was also an ardent abolitionist with strong political connections. All this easily earned him a commission as Colonel of the Third U.S. Cavalry. On May 17, 1861, he was appointed brigadier general, in command of the 2d Division in Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell's army. Promoted to major general on August 13, 1861, he took part in the First Battle of Bull Run, in which he was seriously wounded.

His rapid advancement in rank was aided by Congressman Isaac Arnold, who served with Hunter at the First Battle of Bull Run. Hunter's ambition was greater than his ability; Mr. Lincoln often had to use considerable tact to get his cooperation. When in September 1861, President Lincoln ordered Hunter to St. Louis, he used the great diplomacy: "Gen. Fremont needs assistance which it is difficult to give him. He is losing the confidence of men near him, whose support any man in his position must have to be successful. His cardinal mistake is that he isolates himself, & allows nobody to see him; and by which he does not know what is going on in the very matter he is dealing with. he needs to have, by his side, a man of large experience. Will you not, for me, take that place? Your rank is one grade too high to be ordered to it; but will you not serve the country, and oblige me, by taking it voluntarily?"

Hunter was briefly put in charge of Fremont's command. He was later disgruntled to be ordered to command the Army of the West centered on Kansas. In that position, he had to work with Senator Lane in recruiting Indian troops to fight for the Union. As often happened with military peers and subordinates, he quarreled with Lane.

Later, as Commander of the Department of the South (March 31-August 22, 1862) operating on the Carolinas coast, he besieged Fort Pulaski (Georgia) and issued his own emancipation edict on May 9, 1862, proclaiming the freedom of slaves in Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina. Lincoln, determined to maintain his executive prerogatives, promptly nullified Hunter's order and reprimanded his overzealous general. That reversal may have influenced an opinion Hunter expressed in early October 1862 at Salmon P. Chase's home that President Lincoln was a "man irresolute but of honest intentions—born a poor white in a Slave State, and, of course, among aristocrats—kind in spirit and not envious, but anxious for approval, especially of those to whom he has been accustomed to look up [to]—hence solicitous of support of the Slaveholders in the Border States . . ."

In South Carolina General Hunter organized the Union Army's first Negro regiment, the 1st South Carolina, which was approved by Congress, and was soon described by the Confederacy as a "felon to be executed if captured." Not merely a political liability, Hunter also proved to be an incompetent combat commander. In June of 1862, while trying to capture Charleston, South Carolina, Hunter was defeated at Secessionville. After the defeat, he was suspended from duty temporarily.

When Grant took charge of the army, Hunter replaced Franz Sigel as commander of the Department of West Virginia (May 21, 1864). In this capacity he was instructed to help shield Washington, lay waste to the Shenandoah Valley (breadbasket of Lee's army), and draw some of Lee's forces away from Richmond. Hunter was effective in the destruction of civilian property, burning countless farms and homes—earning himself a reputation for viciousness and hatred from Southerners—but inept in engagements with enemy troops. After pillaging the Shenandoah Valley and sacking Lexington, Hunter headed for Lynchburg in June 1864. There, on June 18, a smaller force led by Jubal Early easily sent Hunter into a hasty retreat to the safety of West Virginia (not before John McCausland added one more blemish to Hunter's record, Hanging Rock, where he lost a third of his artillery).

Not even Hunter's political connections were enough to offset his combat failures, and after a meeting with Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan, Hunter resigned his command on August 8, 1864. Sheridan was then able to clear the Shenandoah Valley of Confederate troops.

At the end of the war, Hunter oversaw President Lincoln's funeral and escorted President Lincoln's body back to Springfield. Later, he presided at trial of those charged with conspiring to murder the President.

He retired as a colonel of the cavalry, with brevets of brigadier and major general, in 1866, and lived in Washington, D.C. until his death, on February 2, 1866.

Hunter graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., in 1822 and was assigned to frontier duty at Fort Dearborn, Illinois. He resigned in 1836 and spent six years in real estate before returning to the army as paymaster with the rank of major. He served as Major Paymaster during the Mexican War. A Whig turned Democrat and a one-time Chicago businessman, he was a professional soldier before the Civil War but because he served as a paymaster, lacked real military experience.

Hunter graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., in 1822 and was assigned to frontier duty at Fort Dearborn, Illinois. He resigned in 1836 and spent six years in real estate before returning to the army as paymaster with the rank of major. He served as Major Paymaster during the Mexican War. A Whig turned Democrat and a one-time Chicago businessman, he was a professional soldier before the Civil War but because he served as a paymaster, lacked real military experience.