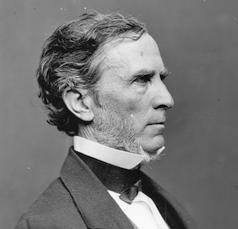

William Pitt Fessenden (1806-1869)

William Pitt Fessenden (October 16, 1806 - September 8, 1869) was born in 1806 in Merrimack County, New Hampshire. He graduated from Bowdoin College in 1823, studied law, was admitted to the state bar in 1827, and began practicing in Maine practicing with his father Samuel Fessenden, who was also a prominent anti-slavery activist. Fessenden was a Whig (later a Republican) and member of the Fessenden political family. He was a member of the legislature of that state in 1832, and its leading debater. He was noted for his swiftness of retort. He refused nominations to congress in 1831 and in 1838, and served in the legislature again in 1840, becoming chairman of the house committee to revise the statutes of the state.

He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives as a Whig in 1840, serving one term (1841 to 1843), during which time he moved the repeal of the rule that excluded antislavery petitions, and spoke upon the loan and bankrupt bills, and the army. Fessenden decided not to run for reelection and returned home to Maine, where he gave his attention to his law business until he served in the state legislature again from 1845 to 1846. He was a member of the Whig national conventions that nominated Harrison (1840), Taylor (1848), and Scott (1852).

He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives as a Whig in 1840, serving one term (1841 to 1843), during which time he moved the repeal of the rule that excluded antislavery petitions, and spoke upon the loan and bankrupt bills, and the army. Fessenden decided not to run for reelection and returned home to Maine, where he gave his attention to his law business until he served in the state legislature again from 1845 to 1846. He was a member of the Whig national conventions that nominated Harrison (1840), Taylor (1848), and Scott (1852).

He acquired a national reputation as a lawyer and an antislavery Whig, and in 1849 prosecuted before the Supreme Court an appeal from an adverse decision of Judge Story, and gained a reversal by an argument which Daniel Webster pronounced the best he had heard in twenty years. He was again in the state legislature in 1853 and 1854.

He was elected in 1854 to the United States Senate with the support of Whigs and Anti-Slavery Democrats. Taking his seat in February 1854, he made, a week afterward, an electric speech against the Kansas Nebraska bill, which placed him in the front rank of the Senate. He took a leading part in the formation of the Republican Party, and from 1854 till 1860 was one of the ablest opponents of the proslavery measures of the Democratic administrations. His speech on the Clayton-Bulwer treaty, in 1856, received the highest praise, and in 1858 his speech on the Lecompton constitution of Kansas, and his criticisms of the opinion of the Supreme Court in the Dred Scott case, were considered the ablest discussion of those topics. He was reelected to the senate in 1859 without the formality of a nomination. In 1861 he was a member of the Peace congress.

By the secession of the southern senators the Republicans acquired control of the Senate, and placed Fessenden at the head of the Finance Committee, where he served as chairman during the 37th through 39th Congresses (1861-1864). During the Civil War he took a leading part in framing measures relating to revenue, taxation, and appropriations and sustaining the national credit. He opposed the Legal Tender Act as unnecessary and unjust. Senator Sumner declared that he was "in the financial field all that our best generals were in arms." He also served as a chairman of the Committee on Public Buildings and Grounds during the 40th Congress, the Appropriations Committee during the 41st Congress and the U.S. Senate Committee on the Library, also during the 41st Congress.

He remained in the Senate until 1864 when, upon Salmon P. Chase's resignation as the 25th Secretary of the Treasury, President Lincoln promptly appointed Fessenden to be the 26th Secretary of the Treasury. The situation was dark. Chase had just withdrawn a loan from the market for want of acceptable bids and the capacity of the country to lend seemed exhausted. The currency had been enormously inflated, and gold was at 280. Reluctant to take the position of Secretary due to ill health, Fessenden succumbed to Lincoln's wishes when Lincoln told him "that the crisis demanded any sacrifice, even life itself." He served from July 5, 1864 until March 3, 1865.

Upon assuming office Fessenden was immediately faced with the government's need for money. When his acceptance became known, gold fell to 225, with no bidders. He declared that no more currency should be issued, and, making an appeal to the people, and with the aid of Civil War financier Jay Cooke, Fessenden marketed several successful short-term loans bearing exceptional interest rates that were well subscribed to by the American people. He prepared and put, upon the market the "seven thirty" loan, which proved a triumphant success. This loan was in the form of bonds bearing interest at the rate of 7.30 per cent, which were issued in denominations as low as $50, so that people of moderate means could take them. He also framed and recommended the measures, adopted by Congress, which permitted the subsequent consolidation and funding of the government loans into the 4 and 4 1/2 percent bonds. During Fessenden's term, the problem created by the inflationary greenbacks, first issued in 1863, began to emerge. Debate would rage for the rest of the century over replacing them with currency backed by specie or taking advantage of the inflationary soft money during periods of expansion.

Fessenden's tenure in the cabinet lasted only eight months. The financial situation becoming favorable, Fessenden, in accordance with his expressed intention, resigned to resume his duties as a United States Senator from Maine. He was again made chairman of the Finance Committee, and chairman of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction in December 1865. He wrote most of its famous report, which vindicated the power of Congress over the rebellious states, showed their relations to the government under the Constitution and the law of nations, and recommended the constitutional safeguards made necessary by the rebellion. Although he believed Congress, and not the President, should direct Reconstruction, and although he disliked Andrew Johnson personally, he refused to vote for Johnson's impeachment—one of only seven Republican senators to do so. He also refused to vote on the Tenure of Office Act and in general acted more moderately than his fellow radical Republicans. His course, particularly in regard to the impeachment proceedings, was contrary to the expressed wishes of his constituency, and for a time he was unpopular. He was subjected to storm of detraction from his own party. His last service was in 1869, and his last speech was upon the bill to strengthen the public credit. He advocated the payment of the principal of the public debt in gold, and opposed the notion that it might lawfully be paid in depreciated greenbacks. Although his party shunned him, Fessenden served in the Senate until his death in 1869. He died in Portland, Maine, September 8, 1869

For several years he was a regent of the Smithsonian institution. He received the degree of LL.D. from Bowdoin in 1858, and from Harvard in 1864.

Two of his brothers, Samuel C. Fessenden and T.A.D. Fessenden, were also Congressmen. He had three sons who served in the American Civil War: Samuel Fessenden, killed at the Second Battle of Bull Run, and Brigadier-General James D. Fessenden and Major-General Francis Fessenden, the latter of whom wrote a two-volume biography of his father which was published in 1907.

He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives as a Whig in 1840, serving one term (1841 to 1843), during which time he moved the repeal of the rule that excluded antislavery petitions, and spoke upon the loan and bankrupt bills, and the army. Fessenden decided not to run for reelection and returned home to Maine, where he gave his attention to his law business until he served in the state legislature again from 1845 to 1846. He was a member of the Whig national conventions that nominated Harrison (1840), Taylor (1848), and Scott (1852).

He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives as a Whig in 1840, serving one term (1841 to 1843), during which time he moved the repeal of the rule that excluded antislavery petitions, and spoke upon the loan and bankrupt bills, and the army. Fessenden decided not to run for reelection and returned home to Maine, where he gave his attention to his law business until he served in the state legislature again from 1845 to 1846. He was a member of the Whig national conventions that nominated Harrison (1840), Taylor (1848), and Scott (1852).