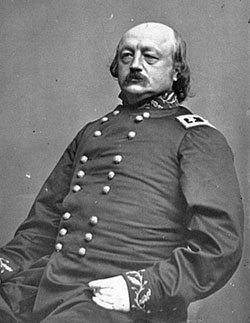

Benjamin F. Butler (1818-1893)

Benjamin F. Butler (born , Nov. 5, 1818, Deerfield, N.H., U.S., died Jan. 11, 1893, Washington, D.C.) American politician and army officer during the American Civil War (1861-65) who championed the rights of workers and black people.

A prominent attorney at Lowell, Mass., Butler served two terms in the state legislature (1853, 1859), where he distinguished himself by vigorously supporting the cause of labour and of naturalized citizens. Butler ran unsuccessfully for governor of Massachusetts in 1860 as a Breckinridge Democrat. Though he was affiliated with the Southern wing of the Democratic Party and supported John Breckinridge for President in 1860 after earlier supporting Jefferson Davis for the Democratic nomination, he strongly supported the Union after the Civil War broke out. He was appointed a Union officer for political reasons, and his military career was mercurial and often controversial. After the fall of Fort Sumter, he became a brigadier general of the Massachusetts militia and subsequently took military control of Baltimore in May 1861. His peremptory exercise of authority led to his removal by Gen. Winfield Scott.

A prominent attorney at Lowell, Mass., Butler served two terms in the state legislature (1853, 1859), where he distinguished himself by vigorously supporting the cause of labour and of naturalized citizens. Butler ran unsuccessfully for governor of Massachusetts in 1860 as a Breckinridge Democrat. Though he was affiliated with the Southern wing of the Democratic Party and supported John Breckinridge for President in 1860 after earlier supporting Jefferson Davis for the Democratic nomination, he strongly supported the Union after the Civil War broke out. He was appointed a Union officer for political reasons, and his military career was mercurial and often controversial. After the fall of Fort Sumter, he became a brigadier general of the Massachusetts militia and subsequently took military control of Baltimore in May 1861. His peremptory exercise of authority led to his removal by Gen. Winfield Scott.

In May 1861 he was promoted to the rank of major general in command of Fort Monroe, Virginia. There, his seizure of three runaway slaves as "contraband" led to a crisis about the government's treatment of escaped slaves and a growing reputation as a radical. One day in late May, three slaves who had been laboring on Confederate defenses had come through the lines to seek refuge among the Federals. The men's owner, Charles Mallory, demanded their return under the Fugitive Slave Law. The irregular conditions of the rebellion were not lost on Butler. To Butler, Mallory's claim on the three blacks was bizarre, since if Virginia asserted that it was no longer part of the Union, how Virginians claim the right to invoke Federal laws? Furthermore, Mallory was a Confederate colonel, engaged in military operations against the Federal authority. It seemed to Butler that the United States government had a right to seize the property of those in active rebellion against it. Since the three men were legally property, the government was therefore entitled to seize them and use them as it saw fit. Butler did so, putting them to work on building up his own defenses. The slaves were "contraband of war". Soon hundreds of escaped slaves, or "contrabands", were making their way into Fortress Monroe, where they were put to work as paid laborers. Secretary of War Cameron approved Butler's action, even though the bizarreness of the situation cut both ways: if the Federal government did not recognize the secession of the state of Virginia, then the Fugitive Slave Act was still valid. Once again, however, if the rules were slippery, the Federal government had few problems selecting among them as convenience dictated. The U.S. Congress would eventually, in August 1861, endorse this position with a cautiously worded Confiscation Act, which allowed US military commanders to liberate slaves being used by Confederate military forces. This was a half-step, but one that was not so faint as it sounded.

In early June 1861, Butler found out that the rebels were setting up a battery of artillery at a river crossing about 8 miles (13 kilometers) from Butler's lines, near a church named Big Bethel, and decided to deal with it. Butler's plan involved complicated movements of seven Federal regiments against about 1,400 Confederates. The troops went into action in the darkness on 9 June 1861 and the result was mass confusion, with Union soldiers firing on each other and providing the rebels with an entertaining "rabbit shoot". By the end of the next day, the Federals had lost 76 dead and wounded, the Confederates only 8. Although painful to the Union soldiers who took the worst of it, the fight at Big Bethel was of little consequence, except as an occasion for Confederate jubilation and Union humiliation. Butler was clearly no military genius.

To make the blockade of the southern coasts effective and to prevent privateering, a joint naval and military expedition under Flag Officer Silas Stringham and Army Major Benjamin F. Butler was sent out to take key positions on the coast. On August 26 1861, the Federal fleet left Hampton Roads and headed south. The flotilla was led by the powerful wooden steam frigates Minnesota and Wabash and the smaller Susquehanna, along with two other steam warships and an antique sail frigate, a revenue cutter, two chartered merchantmen with 900 soldiers on board, and a tugboat named Fanny. The fleet's target was a narrow gap in the middle of the barrier island chain named Hatteras Inlet, which was guarded by two makeshift forts, Fort Clark and Fort Hatteras. Fort Clark had only five guns; Fort Hatteras was bigger and better-designed, with roughly 20 guns, but they were of small caliber and their powder supply was defective. On the morning of Wednesday, August 28, the fleet drew up along the shore from the forts and began to pound them. A gale blew up in the evening, forcing the ships to withdraw, but troops were rashly landed anyway until the weather got so rough the operation could not be continued, leaving about 300 men stranded on the island without hope of support. Fortunately for the Federals, the Confederates didn't feel confident enough to attack them. By the morning the seas had subsided and the bombardment continued.

The Confederates were taking a pounding and their own return fire was ineffective. At noon they called it quits and surrendered. The rebels refused to surrender to the landing force, however, arguing that it was the navy that had defeated them and that the soldiers couldn't have taken the forts in a year. The Federals were flexible on this point of pride, and allowed the rebels to surrender to the "armed forces" of the United States. Two regiments and some of the smaller warships were left there while the fleet returned to Hampton Roads for reinforcements. When they arrived, Butler hurried to Washington. He got hold of Montgomery Blair and Gustavus Fox, and all three men went to the White House and roused Abraham Lincoln out of bed at midnight. Butler later claimed that Lincoln, still in his nightshirt, was so ecstatic at the news that the President and Fox danced merrily around the room. The Confederates were as dejected as Lincoln was elated. There was nothing they could do to eject the Federals, and the Yankess could obviously move at will against any point on the North Carolina coast. A newspaperman in Raleigh wrote: "The whole of the eastern part of the state is now exposed to the ravages of merciless vandals . . . Our state is now plunged into a great deal of trouble."

Early in 1862 Butler was given command of the land forces that accompanied the victorious Union expedition against New Orleans. The city fell late in April, and from May to December Butler ruled it with an iron hand, earning Butler the nicknamed "Beast Butler". He executed a citizen who had torn down the U.S. flag, undertook sanitary measures to prevent an outbreak of yellow fever, and confiscated the property of Confederate sympathizers. Partly because of difficulties arising from his relations with foreign consuls concerning confiscated property, he was recalled at the end of the year. He was frequently surrounded by the aura of corruption although his personal involvement was never proven.

In 1863, he was named to command the Department of Virginia and North Carolina and in 1864 he was put in charge of Union efforts to control potential Election Day riots in New York City.

As commander of the Army of the James in Virginia in 1864, Butler became bottled up in Bermuda Hundred, Va., and was unsuccessful in operations before Richmond and Petersburg, Va. After the failure of an expedition against Fort Fisher, North Carolina, he was relieved of his command (January 1865).

He frequently visited the White House between military appointments. William O. Stoddard recalled the first visit in April 1861: "I never saw him wear quite so much uniform as he did when, in 1861, he came up to pay his respects to the President as a commander of Massachusetts militia. He then wore the full uniform of a Bay State militia major general, and a wonderful disguise it was, with a vast amount of sash, mountainous epaulets and a scythe sword with a railway curse in it. The cocked hat was also a curiosity of war—or peace." Regardless of his uniform, Butler was always aware of his own self-importance "Nobody ever doubted his energy; nearly everybody doubted his character. He was endlessly useful and endlessly troublesome. Only a Dickens could do justice to his remarkable combination of gifts, faults, and picturesque anfractuosities," wrote historian Allan Nevins.

On one occasion, General Butler complained to Mr. Lincoln about desertions. "Mr. President," said Butler, "the bounties which are now being paid to new recruits cause very large desertions. Men desert and go home, and get the bounties and enlist in other regiments.' 'That is too true,' he replied, 'but how can we prevent it?' 'By vigorously shooting every man who is caught as a deserter until it is found to be a dangerous business.' A saddened, weary look came over his face which I had never seen before, and he slowly replied, 'You may be right—probably are so; but God help me, how can I have a butcher's day every Friday in the Army of the Potomac?'

As one of the army's most prominent political generals, he had the potential to cause political trouble for President Lincoln, especially given his strong relations with Radical Republicans in Congress. Mr. Lincoln used former War Secretary Simon Cameron to sound out Butler's political intentions in 1864. Butler denied presidential ambitions and the President tried to keep him happy with other military employment until General Grant removed him from command in early 1865. The President himself considered Butler "as full of poison gas as a dead dog."

After the war, Butler became a Radical Republican in the U.S. House of Representatives (1867-75, 1877-79), supporting firm Reconstruction measures toward the South and playing a leading role in the impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson, serving as one of seven House impeachment managers. Although a staunch supporter of President Ulysses S. Grant after 1868, he broke with the party in 1878 because of his sympathy with the inflationary Greenback movement. After two unsuccessful tries, he was elected Democratic governor of Massachusetts in 1882 and two years later became the presidential candidate of the Greenback-Labor Party and the Anti-Monopoly Party. He advocated the eight-hour day and national control of interstate commerce but failed to win a single electoral vote.

At various times in his career Butler was accused of corruption, but no charges against him were ever proved. (Encyclopaedia Britannica)

A prominent attorney at Lowell, Mass., Butler served two terms in the state legislature (1853, 1859), where he distinguished himself by vigorously supporting the cause of labour and of naturalized citizens. Butler ran unsuccessfully for governor of Massachusetts in 1860 as a Breckinridge Democrat. Though he was affiliated with the Southern wing of the Democratic Party and supported John Breckinridge for President in 1860 after earlier supporting Jefferson Davis for the Democratic nomination, he strongly supported the Union after the Civil War broke out. He was appointed a Union officer for political reasons, and his military career was mercurial and often controversial. After the fall of Fort Sumter, he became a brigadier general of the Massachusetts militia and subsequently took military control of Baltimore in May 1861. His peremptory exercise of authority led to his removal by Gen. Winfield Scott.

A prominent attorney at Lowell, Mass., Butler served two terms in the state legislature (1853, 1859), where he distinguished himself by vigorously supporting the cause of labour and of naturalized citizens. Butler ran unsuccessfully for governor of Massachusetts in 1860 as a Breckinridge Democrat. Though he was affiliated with the Southern wing of the Democratic Party and supported John Breckinridge for President in 1860 after earlier supporting Jefferson Davis for the Democratic nomination, he strongly supported the Union after the Civil War broke out. He was appointed a Union officer for political reasons, and his military career was mercurial and often controversial. After the fall of Fort Sumter, he became a brigadier general of the Massachusetts militia and subsequently took military control of Baltimore in May 1861. His peremptory exercise of authority led to his removal by Gen. Winfield Scott.