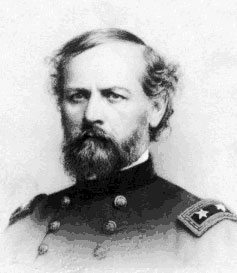

Don Carlos Buell (1818-1898)

Don Carlos Buell (1818-1898) was a career U.S. Army officer who fought in the Seminole War, the Mexican-American War, and the Civil War.

Buell, named for an uncle, was born on March 23, 1818 near Marietta, Ohio. His father was a prosperous farmer and a Catholic, and he died in 1823 in a cholera epidemis. In 1826 Don Carlos was sent to live with an uncle, a prominent farmer and merchant, in Lawrenceburg, Indiana. Buell worked on the farm, but was also given a solid education in a local private school where he excelled in mathematics and horsemanship. His prosperous uncle procured for him admission to West Point where he spent 4 difficult years, coming very close several times to being expelled for excessive demerits, although his academic work was generally at a high level. Buell graduated from West Point in 1841 and was a company officer of infantry in the Seminole War of 1841-42 during which he demonstrated his remarkable administrative abilities and a marked proclivity for enforcing discipline.

Buell, named for an uncle, was born on March 23, 1818 near Marietta, Ohio. His father was a prosperous farmer and a Catholic, and he died in 1823 in a cholera epidemis. In 1826 Don Carlos was sent to live with an uncle, a prominent farmer and merchant, in Lawrenceburg, Indiana. Buell worked on the farm, but was also given a solid education in a local private school where he excelled in mathematics and horsemanship. His prosperous uncle procured for him admission to West Point where he spent 4 difficult years, coming very close several times to being expelled for excessive demerits, although his academic work was generally at a high level. Buell graduated from West Point in 1841 and was a company officer of infantry in the Seminole War of 1841-42 during which he demonstrated his remarkable administrative abilities and a marked proclivity for enforcing discipline.

During the Mexican War he fought under Taylor and Scott, and was brevetted for bravery 3 times. He was described as being stern in expression, formal in manner, and stocky in physique. Sometimes he displayed his arm and upper-body strength by clasping his wife about the waist, holding her off the floor straight out before him, and then lifting her to sit on a mantle. After the Mexican War Buell spent the next thirteen years in the adjutant general's office and was a lieutenant colonel working as an adjutant of the Department of the Pacific when the Civil War broke out. Buell was appointed lieutenant colonel, then brigadier general of volunteers on 17 May 1861, and major general of volunteers on 22 March 1862.

Buell aided McClellan in organizing the Army of the Potomac and was sent, in November 1861, to Kentucky to succeed Sherman in command after the latter had buckled under the responsitility and requested of McClellan that he be relieved. There Buell organized the Army of the Ohio which formed the basis of the future Army of the Cumberland—the most highly trained, successful, and modern army on either side in the Civil War. He was expected to liberate East Tennessee at the same time that he protect Louisville and take Nashville. He opted for Nashville and occupied it unopposed on February 25, 1862, believing that he didn't have the forces necessary for control of all of Tennessee and that Nashville was militarily more important.

In the spring of 1862 he pursued the retiring Confederates under General Sidney Johnston toward Mississippi. Buell then saved Grant at the battle of Shiloh, arriving with 30,000 fresh troops which turned the tide the second day of the battle. In doing so he embarrassed Grant and thus incurred Grant's hostility. Afterward Buell served under General Henry W. Halleck in the Union advance on Corinth, after which he was sent to capture Chattanooga. At the same time he was burdened with the repair and protection of hundreds of miles of railroad while being constantly harassed by Confederate Cavalry. He resisted interference from politicians and incurred the emnity of Governors Morton of Indiana and Andrew Johnson of Tennessee who wanted control of their states' volunteer forces. Said to be a friend of McClellan, he certainly was a Democrat, favoring gradual emancipation with compensation to the slave owners. This brought him in conflict with an increasingly radical Republican adminstration. He believed in war by maneuver and can be called a "soft war" commander in a conflict which steadily hardened, although the merits of the "hard war" school are debatable. Buell himself stated that "The object is not to fight great battles, and storm impregnable fortifications, but by demonstrations and maneuvering to prevent the enemy from concentrating his scattered forces." He further stated that "the commander merits condemnation who, from ambition or ignorance or a weak submission to the dictation of popular clamor and without necessity or profit, has squandered the lives of his soldiers."

Although some other military experts were able to appreciate the forward steps being taken and the low casualties, the northern public and politicians were unable to understand or admit the successes of Buell's philosophy. He is also often characterized as having been cold and aloof and lacking in the common touch needed to motivate volunteer soldiers. There was never any serious doubt about Buell's loyalty to the Union, but the fact that he was a former slave owner himself (he had inherited eight slaves when he married the widow of a fellow officer in 1851) left him open to charges that he was a Southern sympathizer. Buell did not help his cause when he strictly enforced a policy of noninterference with Southern civilians while campaigning in Alabama and Tennessee in mid-1862. The situation reached a head in May 1862, when Colonel John Basil Turchin permitted his soldiers to pillage the town of Athens, Ala., after it was rumored that Athens citizens had helped Confederate guerrillas derail a Union supply train. The subsequent destruction infuriated Buell, whose guiding tenet had always been iron discipline and gentlemanly comportment. He brought charges against Turchin of neglect of duty, conduct unbecoming an officer and disobedience of orders. Turchin was convicted of the most serious charges and sentenced to be dismissed from the Army. However, Turchin was reinstated by the War Department and promoted to brigadier general.

Lincoln eventually gave in to the political pressure and ordered Thomas to replace Buell on September 30, 1862. Amazingly, Thomas refused the command, and Lincoln suspended the order. This took place during the contest for position between Buell and Bragg in Kentucky as Bragg was trying to threaten Louisville and establish a Confederate state government at Frankfort. Thomas stated that it was improper to suspend a commander before imminent battle, but more probably he had no desire to be directly exposed at that time to politically motivated attacks. Meanwhile the exhortations from the administration continued unabated, as the following message to Buell from Halleck of October 23, 1862 demonstrates: "It is the wish of the Government that your army proceed to and occupy East Tennessee with all possible dispatch. It leaves to you the selection of the roads upon which to move to that object; but it urges that this selection be so made as to cover Nashville and at the same time prevent the enemy's return into Kentucky. To now withdraw your army to Nashville would have a most disastrous effect upon the country, already wearied with so many delays in our operations....Neither the Government nor the country can endure these repeated delays. Both require a prompt and immediate movement toward the accomplishment of the great object in view—the holding of East Tennessee."

The long period of maneuvering ended in the bloody but indecisive Battle of Perryville, precipitated by a minor engagement over sources of then scarce water. Only parts of both armies were engaged due to breakdowns in command and communications on both sides. The result nevertheless pushed Bragg back into Tennessee and definitively brought Kentucky under Union control. The alleged tardiness of Buell's pursuit and his objections to an unrealistic plan of campaign ordered by the Washington authorities brought about his replacement by Rosecrans. Note that almost no post-battle pursuit on either side during the Civil War was successful. The complaints made against him were investigated by a military court of inquiry in 1862-63, but the jury could agree only on a mild censure for errors during the battle. This verdict did not satisfy Halleck and the government prosecutor, and the inconclusive result was not published. Nevertheless, Buell was thereafter sidelined and not again offered significant duty.

General William Farrar "Baldy" Smith, one of the Union's most respected generals, described Buell in his unpublished memoirs as "a capital soldier and a student in his profession. He fought a battle with courage, coolness, and intelligence, saving us from utter rout at Shiloh, into which false position Halleck's ambition and Grant's density had begotten us."

After waiting in Indianapolis a year for orders, Buell resigned his volunteer commission in May 1864 and his regular commission in June 1864.

After the war he settled in Kentucky, where he engaged in coal mining and became president of the Green River Iron Company, and in the period 1885-89 he was a government pension agent. He died on November 19, 1898, at his home near Paradise, Kentucky, and was buried in Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri. Buell Armory on the University of Kentucky campus in Lexington, Kentucky, is named for him.

Buell, named for an uncle, was born on March 23, 1818 near Marietta, Ohio. His father was a prosperous farmer and a Catholic, and he died in 1823 in a cholera epidemis. In 1826 Don Carlos was sent to live with an uncle, a prominent farmer and merchant, in Lawrenceburg, Indiana. Buell worked on the farm, but was also given a solid education in a local private school where he excelled in mathematics and horsemanship. His prosperous uncle procured for him admission to West Point where he spent 4 difficult years, coming very close several times to being expelled for excessive demerits, although his academic work was generally at a high level. Buell graduated from West Point in 1841 and was a company officer of infantry in the Seminole War of 1841-42 during which he demonstrated his remarkable administrative abilities and a marked proclivity for enforcing discipline.

Buell, named for an uncle, was born on March 23, 1818 near Marietta, Ohio. His father was a prosperous farmer and a Catholic, and he died in 1823 in a cholera epidemis. In 1826 Don Carlos was sent to live with an uncle, a prominent farmer and merchant, in Lawrenceburg, Indiana. Buell worked on the farm, but was also given a solid education in a local private school where he excelled in mathematics and horsemanship. His prosperous uncle procured for him admission to West Point where he spent 4 difficult years, coming very close several times to being expelled for excessive demerits, although his academic work was generally at a high level. Buell graduated from West Point in 1841 and was a company officer of infantry in the Seminole War of 1841-42 during which he demonstrated his remarkable administrative abilities and a marked proclivity for enforcing discipline.